Hooked

You won’t emerge entirely unscathed from a fly fishing life. At least I haven’t. And I’ve got the scars to prove it.

FLY FISHING is rarely a contact sport, and you’ll seldom see anglers come to blows. Far less blood is shed, accidentally or intentionally, in fly angling than in most other leisure activities. We fish “fine and far off,” as they say, with hooks daintily dressed with fur and feathers rather than, say, gobs of worms, which on some days would almost surely catch more trout. We’re a genteel tribe — Renaissance people with rods.

Sometimes to a fault. On the more bourgeois edges of the sport, one is pampered in a distant lodge where a week’s stay can require remortgaging one’s house; where wine pairings at dinner are given equal emphasis with matching the hatch on the water; and where one otherwise uses the pronoun “one” to describe oneself.

That kind of Chablis-soaked expedition, in which guides are made to mother and smother high-paying clients of questionable competence, can give the entire enterprise a deserved elitist rap. The only time I extend my pinky, ever, is when I’m retrieving a nymph hand over hand. At its essence, fly fishing offers solitude and a kind of workmanlike simplicity, and I’ve always been happy as a clam steering well clear of the posh Pardon me but do you have any Grey Poupon set. For me, a leisurely lunch streamside during a lull in the action is sublime. Nibbling on the cheese sandwich I’d stashed in the back of my vest and sipping from a lukewarm can of craft beer (nonalcoholic these days, but that’s another story) is better than a banquet. That my personal fly fishing aesthetic conveniently reflects my tax bracket is just a coincidence, right?

OK, but there are occasionally clear and present dangers. For starters, you can drown, and that’s no joke. On any number of American rivers with a good head of water in them, go in over your waders in pursuit of a rising trout just beyond range of a decent cast and presentation, and you may not live to tell the tale.

The closest truly blue-ribbon trout water to me is the Swift River in my home state of Massachusetts. Its headwaters are in the shadow of the mighty Quabbin Reservoir, which supplies drinking water to Boston and a large swath of the western part of the Commonwealth. On my last outing to the Swift, I passed by another Massachusetts trout lake with a mouthful of a name: Lake Chargoggagoggmanchauggagoggchaubunagungamaugg. In the early 1900s, a local newspaper editor, citing a supposed Native American treaty that settled fishing rights to the lake, claimed to have documented research supporting his translation of the meaning of that 45-letter, 14-syllable name: “You fish on your side, I fish on my side, and nobody fishes in the middle.” Later, the editor admitted he’d concocted all of that from pure imagination, and scholars say a more accurate translation would be: “English knifemen and Nipmuc Indians at the boundary or neutral fishing place.” But the original name stuck, as these things tend to do, although in what seems to have been an elaborate practical joke, it was only slightly shortened to Lake Chaubunagungamaug. Locals with no poetry in their souls call it Webster Lake.

I’ve never tried it myself, but I’m told it fishes best from — you probably guessed it — the middle.

Hatches come off like clockwork on the upper reaches of the cold-water, bottom-draw Swift, a gin-clear tailwater known for its muscular rainbows and a healthy native population of brookies so brilliantly bejeweled they can take your breath away. For two and a quarter miles below Winsor Dam, the Swift is special regulations water — fly fishing only, catch and release — and there, it is southern New England’s answer to Montana’s Madison.

There’s a catch, though, beyond the heavy fishing pressure and the subsequent need to fish technically with unforgiving precision and gossamer tippets: The Massachusetts Water Resources Authority releases a minimum of 20 million gallons a day from the Quabbin into the Swift via the dam’s gates and spillway. There are large, forbidding signs everywhere warning anglers, and the state publishes its release schedule online, but every now and then a fisherman lingers a little too long over a trout and doesn’t clamber to higher ground in time to escape the sudden onslaught of white water.

What we now term “situational awareness” used to be called common sense, and in a more cynical moment, I’d be tempted to list the occasional victims among the ever-growing ranks of Darwin Awards winners. Still, it’s impossible not to feel sorry for these guys, if only because I’ve made more than my own share of bone-headed mistakes over a lifetime of fishing. So far, none has been fatal, but that’s probably ascribable as much to dumb luck as to any restraint or finesse on my part. I do, however, know when it’s time to walk away — or in this case, waddle away as quickly and as dignified as chest waders will allow — from a rising trout.

Of all of nature’s four basic elements — Earth, wind, fire, and water — wind is far and away the angler’s worst enemy.

Lightning is another menace, and there’s a reason why you’ll always hear meteorologists and public safety professionals warn that if you can hear thunder, you can be struck by a bolt from the blue. My brother once lingered on a lake as a storm drew near because the fishing had suddenly become electric, and he wound up cowering in his canoe and very nearly soiling himself as strikes of three hundred million volts apiece rained down around him. On another occasion, my father and I were fishing for wild brookies on the gin-clear Squannacook River near the border separating Massachusetts and New Hampshire when lightning struck within a hundred feet of us. We hit the deck, trembling, and after the squall passed, found what was left of the oak that had absorbed the blow. It was reduced to kindling when the bolt caused the sap within to boil in a fraction of a second, blowing the tree apart. At its base lay the charred remains of a robin’s nest — the mother bird and her four young flash-fried into McNuggets.

Just getting to the general vicinity of where you want to fly fish can be hazardous. I once heard of a single-engine float plane carrying a fishing party that disappeared entirely beneath the tree canopy in the remote outer reaches of Canada’s Northwest Territories, a massive and largely trackless 520,000-square-mile wilderness that’s nearly twice the size of Texas. This is a place that could comfortably accommodate four hundred thousand Central Parks, so it’s probably no surprise that they were never heard from again. I’d like to think they survived and remain on the fishing trip of a literal lifetime, surviving as hunter-gatherers on fiddlehead ferns and hog rainbows caught with dry flies — trophies longer than the white beards that now reach to their knees. Sure, they could have bushwhacked their way back to civilization long ago, but the fishing was too good, and they had the perfect alibi for waiting wives or girlfriends. Much more likely is that they didn’t make it and their skeletons have long ago been picked clean by scavenging wolves and grizzlies.

What? Yes, I have a dark side, and no, I never said I was one of REM’s shiny happy people holding hands.

But I digress. My point is that you won’t emerge entirely unscathed from a fly fishing life. At least I haven’t. And I’ve got the scars to prove it.

___

OF ALL OF nature’s four basic elements — Earth, wind, fire, and water — wind is far and away the angler’s worst enemy.

Maddeningly, it can also be your best friend, particularly if you’re fishing salt or still water. Wind roils the surface in a way that gives fish cover from predators and emboldens them, and it knocks insects out of the air and into the water, stimulating the bite. On lakes and ponds, fishing the lee shore to which the wind is pushing floating mats of vegetation and insect life is a proven technique, especially in those liminal spaces at the edges of weed beds, foam, and dropoffs where trout and bass congregate and feed like fat Americans inhaling fries at a fast food drive-thru.

But wind can tie elaborate knots in your leader; wreak absolute havoc with your presentation to a finicky fish that will bolt at the first inkling of an unnatural drift; and just generally sabotage any attempt at delivering a fly without slapping the water and scaring the spots off every trout in the pool.

If you’re fishing a larger fly like a weighted streamer, you can suddenly find yourself cringing and ducking as the terminal end of your tackle whizzes within millimeters of your head on your backcast and again as you double-haul to punch through the headwind. A tailwind isn’t much better; it can help you gain distance as you shoot your line out to a distant riser, but it can also send your fly slamming painfully into the back of your skull. The suspense is almost unbearable.

This is why we wear hats, not to be fashionable but for protection. There are times when I’ve pined for a pith helmet instead of my usual cotton baseball cap, which is a flimsy shield against a No. 6 Woolly Bugger tied with a few turns of lead or, God forbid, a tungsten bead head. There’s nothing like one of those depth charges striking the occipital bone at the back of your cranium at thirty miles per hour. As Capt. Quint famously said in the movie JAWS, that can make you wish your father never met your mother.

I knew I had no business fly fishing New York’s trouty Croton River on a gusty afternoon, but I had the day off and I hadn’t wet a line in weeks. You know how it is. So, against my better judgment, I ventured astream.

The Croton River Watershed is an unsung treasure — one I discovered in the early 1990s when I was an editor on the foreign desk of The Associated Press. At the time, I worked a four-day overnight shift that strained my marriage but was an angler’s dream: I’d clock in at AP headquarters in midtown Manhattan at 10 p.m. on Sundays, work until 8 a.m., and rinse/repeat until Thursday mornings, when I’d be off until the next Sunday. We lived way up the Hudson River in the city of Peekskill, and I’d often spend a couple of hours on one of the watershed’s dozen or so lakes and streams before grabbing some sleep. There was a lot to choose from: The drainage spans three hundred and fifty square miles of Putnam and Westchester counties, with pristine reservoirs that serve as New York City’s drinking water supply.

Bald eagles circle over water that in some places supports a healthy self-sustaining population of brookies and browns. On the Croton’s East Branch, local angling legend Al Case swished a Gray Ghost streamer through a deep pool called the Phoebe Hole and landed a brown three ounces shy of eleven pounds that set a world record for four-pound test tippet. This is a fishery just twenty-two miles north of my newsroom at glittery Rockefeller Plaza, and as a nocturnal journalist, I had it all to myself on weekdays. It was, in a word, intoxicating.

Work on the imposing New Croton Dam, with its distinctive crowning aqueduct, began in 1892 and was completed in 1906. Its predecessor, the Old Croton Dam, was finished half a century earlier as the first large-scale masonry dam in the United States, and it was copied widely across the eastern US. As usual, the building of the original dam was accompanied by total chaos — then and today the price of progress. Four entire towns along with four hundred farms and dozens of homes, barns, churches, schools, and mills were condemned and taken over. Pretty much everything in what is now downstream was displaced, including not only the living but the dead: Fifteen hundred bodies were exhumed from six cemeteries and relocated along with their tombstones.

On the plus side, the dam created a productive year-round tailwater fishery. Early one morning, while decompressing after a long night of editing, I took an 18-inch holdover brown on a No. 16 pheasant-tail nymph in one of the big pools at the foot of the dam. I whooped as I landed the big fish, but even if I’d had an audience, no one could have heard me over the thundering of the water cascading down the stair-step spillway. The trout’s sides were the color of burnt butter, with black and crimson spots and a slightly kyped jaw.

It was a couple of years later that I found myself a half mile downstream, gripping my rod with one hand and my cap with another to keep the wind from tearing it off my head. Conditions were less than optimal, as anglers like to say, but I zeroed in on the splashy rises in the tail of a fifty-yard riffle, cinched the notched plastic strap on the back of my hat so tightly I could feel my pulse in both temples, and settled in. Even this far from the dam, puffs of mist from the spillway periodically wettened my cheeks.

Positioning myself downstream and a good thirty yards across from the rising trout, I tied on a go-to pattern for this stretch of the Croton — a No. 18 Hendrickson dry fly — and false-casted to play out line while calculating the best way to get a drag-free float over the fish. Normally, it’d be pretty straightforward except that I was casting straight into a headwind complicated by diagonal gusts that radiated out from the spillway. Dams, like wildfires, can create their own weather — updrafts, miniature rainbows and tiny swirling tornadoes of spray — and this one seemed to be spawning little microbursts.

My first attempt ended with the fly in my face and coils of line at my feet, where the current peeled them away to my left and my right, ensnaring me in my own tackle. Worried, I glanced upstream but the trout was still rising; a small victory. On the next attempt, I fed out a little more line and punched it well upstream and across, mending the line and achieving what was, under the circumstances, a decent cast. The wind had picked up noticeably by now, obscuring the surface of the river, but through my polarized sunglasses I caught the unmistakable flash of the refusal rise of a good-sized brown: sixteen inches at least, maybe more. For the Croton, this fish was a slab, and I wanted him badly. I rested the pool for what seemed like an eternity but was probably five minutes, tops, and tried again.

I was a competitive distance runner as a younger man, and a disgust for performance-enhancing drugs imprinted on me early. The human organism’s ability to generate its own narcotics-like chemistry, though, has always fascinated me. I’ve come to love the rush of endorphins that create the exercise-induced euphoria known as the runner’s high. Likewise, as an angler, I relish the java-like jolt of adrenaline I sometimes get when a large trout is rising and I haven’t yet done anything stupid to make him stop. In both form and function, adrenaline is better than Ethiopian dark roast.

So I gathered myself, took a few deep breaths to oxygenate my brain — one of my few takeaways from decades of on-again, off-again therapy — and waited between gusts to make attempt No. 3. The execution was as close to perfect as I’m capable of, and in my mind, I took myself from Defcon 3 (heightened readiness) to the more relaxed level of Defcon 4 (Increased intelligence watch and stronger security measures.) The military’s definition of Defcon 5, in case you’re curious, is least severe level of readiness, and I’ve seldom lived or fished there. To my credit, or at least my relief, I’ve also rarely found myself in the angling equivalent of Defcon 2 (The next step to nuclear war) or, God forbid, Defcon 1 (Nuclear war is imminent or has already begun.)

My false casts were flawless, which for me means I didn’t slap the water behind or before me. The wind seemed to have been sucked into a vacuum, and in the resultant stillness, I made my final approach. In my mind, I heard the crackling of a nonexistent control tower as it radioed, “BK-1, you are clear to land,” and my wrist flexed as I shot the line upstream and across, making a slight midair mend to give the fly a little extra runway over the trout.

What happened in the next few nanoseconds will forever be a blur. What I remember is a gust of wind worthy of a Category 5 hurricane hurling my entire line and leader into my face, sinking the fly’s hook deep into the flesh of my nose. I reflexively hollered and tugged at the fly, but that hook was buried right to the bend in my left nostril.

Technically speaking, I was screwed; and naturally, being a grown man, I commenced to flail and curse and scream until I was hoarse. Now it wasn’t just my nose that throbbed but my throat and my arms, so I clambered out of the river and back to my car, and prepared to drive myself to the hospital. Not, however, before cocking the rear-view mirror to study and fully appreciate my predicament.

___

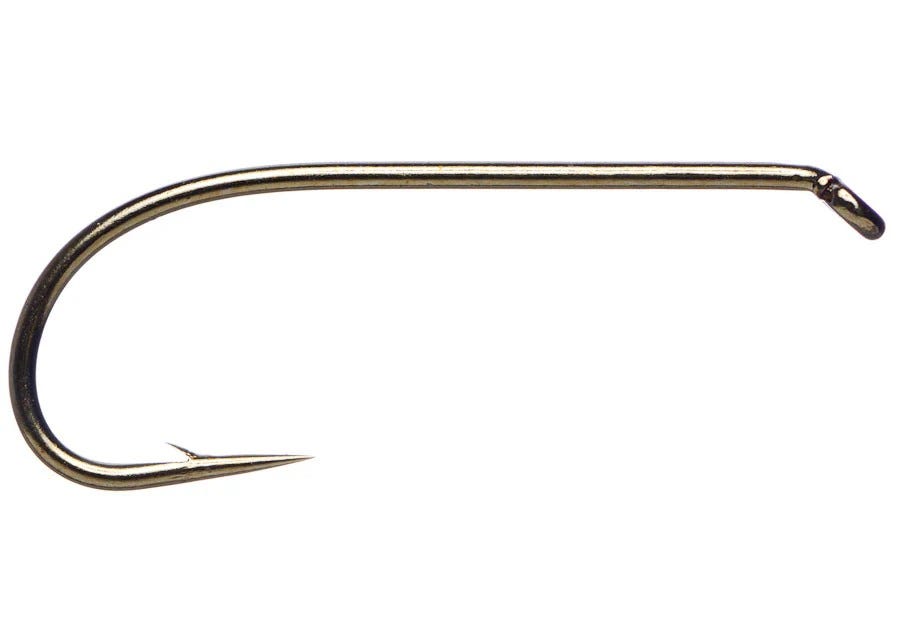

I’VE BEEN hooked before and since, and I’ll surely be hooked again, though I now take elaborate precautions and the sheer fear of it has made me a better caster. For some strange reason, I have yet to fish exclusively with flies tied on barbless hooks, which would take the sting, at least figuratively, out of the equation. When you’re pierced by a barbed hook, the conventional wisdom is to keep pushing the hook through your flesh until the point and barb emerge and can be clipped off with pliers. I challenge anyone to actually do that without passing out.

We were miles over now-dark logging roads from the nearest hospital, and this thing was going to come out only one way, using courage and some single-malt Scotch as a disinfectant.

My most memorable hooking was a freak accident while floating Maine’s Penobscot River for smallmouth bass with my brothers, both lifelong spin fishermen, and our then-preteen sons. Smallies are athletic sport fish that leap high and often, and Brian was battling a nice one that easily would have gone three pounds. We’ll never know for sure because the fish broke the surface and tail-walked before jumping skyward in a spectacular arc and throwing the lure, a jointed minnow bristling with treble hooks, just as Brian instinctively hauled back with a sharp two-handed tug. The lure shot back toward the bow of the boat, and Brian and my son, Nick, ducked as it whizzed overhead, striking me squarely in the chin. “Shit!” my brother exclaimed, but of course he meant losing the fish, not me as collateral damage.

We motored for shore, and back at camp, I teased and tugged at the lure dangling from my jaw. Two barbs were deep in that space below the bottom lip where I’d once against my better judgment grown a soul patch and they weren’t budging. We were miles over now-dark logging roads from the nearest hospital, and this thing was going to come out only one way, using courage and some single-malt Scotch as a disinfectant. I grabbed the lure with a washcloth and ripped it out, hard, instantly turning my chin bright red and the air in our riverside cabin blue. I’m bearded now, partially to conceal the ragged scar, though a friend told me it isn’t too bad and reminds him of Harrison Ford, who has a nearly identical cicatrix in the same spot. He got his in the 1960s by wrapping his car around a telephone pole near Laguna Beach, Calif., so at least I have a better story.

It could have been worse. Dalton, an exuberant young angling friend in Ireland, fly fishes for sea trout at home and abroad. On a windy but productive day prospecting the rugged coastline of Cornwall in southwestern England, a sand eel pattern pierced one of his eyeballs. A selfie of the damage posted on Instagram made me go a little weak in the knees, but I knew he was okay from his wry caption: “Caught a beautiful 5-foot, 11.99-inch, 235-lber this week.” He was back at it the next day, this time wearing protective aviators. I’ve asked him how he did, but for some reason he doesn’t want to talk about it.

___

ALL OF THIS was running through my mind as I drove to the emergency room, the hackled dry fly still lodged in my left nostril. At a traffic light, I could feel someone in a black SUV staring in my peripheral vision, so I had a little fun and swung my face to confront my voyeur, grinning at her maniacally like Jack Nicholson in The Shining. She shrieked, panicked, hit the gas and ran the light.

At New York-Presbyterian Hospital in Croton-on-Hudson, the nurse at the window with the nasal voice and affected blasé demeanor didn’t look up as she typed in my information. She rattled off the usual questions — address and telephone number? primary care physician? insurance card? — before asking what brought me to the ER.

“Trout fly in the nose,” I deadpanned.

That got her attention, and as she met my gaze, her mouth formed a large O. Five minutes later, I was in a triage room.

Fortunately, the ER doctor on duty was also a fly fisherman. I know this because he glanced at me as he entered the room and immediately identified the source of my misery, right down to size and pattern: “Oh, a No. 18 Hendrickson.”

Unfortunately, the doc didn’t practice emergency medicine with the same sportsman’s finesse he surely employed out on the water. I knew I was doomed when he had me lie down, injected my nostril with Lidocain, wrapped a thin cord around the fly, and put one foot up on the gurney as if he were about to start a gas-powered lawnmower. “This may sting,” he warned. Oof. One monumental pull, however, and the fly was out.

That left a scar, too — one no beard will ever hide. The same goes for another in one of my eyebrows. But I’ve long since made my peace with those. I’ve been a fly fisherman for well over half a century, and by the most modest of reckonings, I’ve stuck multiple thousands of trout, salmon, bass, pickerel, perch, and panfish.

Karma, they say, is a bitch — and its hooks aren’t barbless.

This is brilliant storytelling that captures the real price of fly fishing. The way wind transforms from ally to enemy mid-cast is spot-on, I've ducked more streamers than I care to admit and that split-second of terror never gets old. The progression from Defcon ratings to ER visits is genuinly hilarious but also kinda validates why barbless hooks exist.